Challenges in Cancer Research

Cancer remains one of the most formidable challenges in health science, driven by complex cellular ecosystems, dynamic tumour–microenvironment interactions, and genomic complexity. In modern cancer research, three revolutionary sequencing technologies are emerging to address key limitations of traditional approaches: single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and long-read sequencing. Together, they offer deeper resolution, contextual information, and structural clarity that bulk assays simply cannot provide.

This blog will discuss three major challenges in cancer research and show how each of these technologies helps to overcome them.

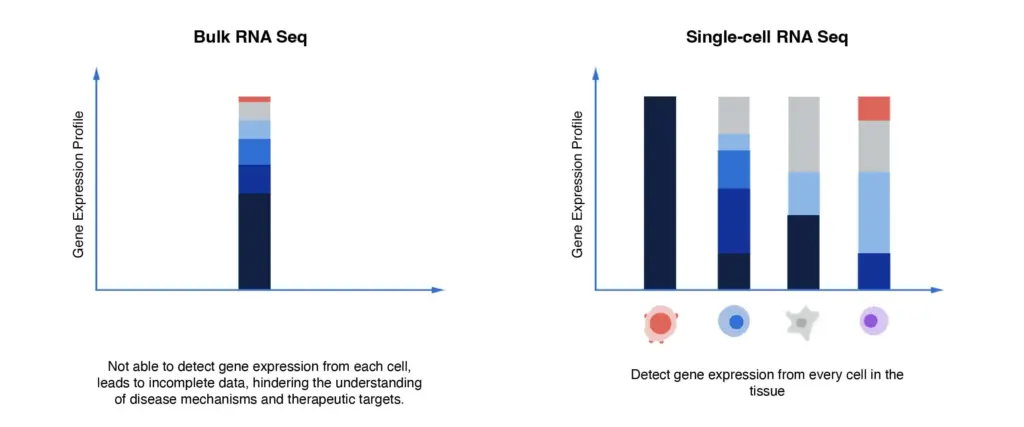

1. Tumour Heterogeneity: Why Bulk RNA Sequencing Falls Short

One of the foundational issues in cancer research is tumour heterogeneity — the fact that within a single tumour mass, there exist multiple genetically and epigenetically distinct cell populations (sub-clones), each potentially behaving differently in terms of growth, metastasis, response to therapy or immune evasion.

The limitation of bulk RNA-seq

Traditional bulk RNA sequencing aggregates RNA from millions of cells, producing an averaged signal which masks rare or minority cell populations. This means that sub-clones responsible for therapy resistance or relapse may go undetected. Bulk approaches cannot resolve cell-to-cell variability, dynamic changes in cell states or trajectory information (for example, from a progenitor-like cell to a more aggressive phenotype).

How single-cell sequencing solves this

Enter single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) (and broader single-cell multi-omics), which profiles the transcriptome of individual cells, allowing for:

-

Detection of rare cell sub-populations which might drive metastasis or recurrence;

-

Mapping of lineage trajectories or state transitions (e.g., stem-like â differentiated tumour cells);

-

Deciphering immune/tumour/stromal cell compositions and their gene signatures at single-cell resolution.

Recent work continues to underscore this. For example, a review of single-cell sequencing in cancer immunotherapy highlights how it reveals intratumoral heterogeneity, distinguishes between malignant and non-malignant cell populations, and elucidates immune microenvironments. PMC

Furthermore, a 2025 article emphasises that single-cell sequencing is transformative in mapping tumour–immune–stromal interactions within the tumour microenvironment. SpringerLink

Key takeaway

For any cancer research project that relies on transcriptomics, if tumour heterogeneity is relevant (which it usually is), single-cell sequencing is now a critical tool — far beyond what bulk RNA-seq alone can provide.

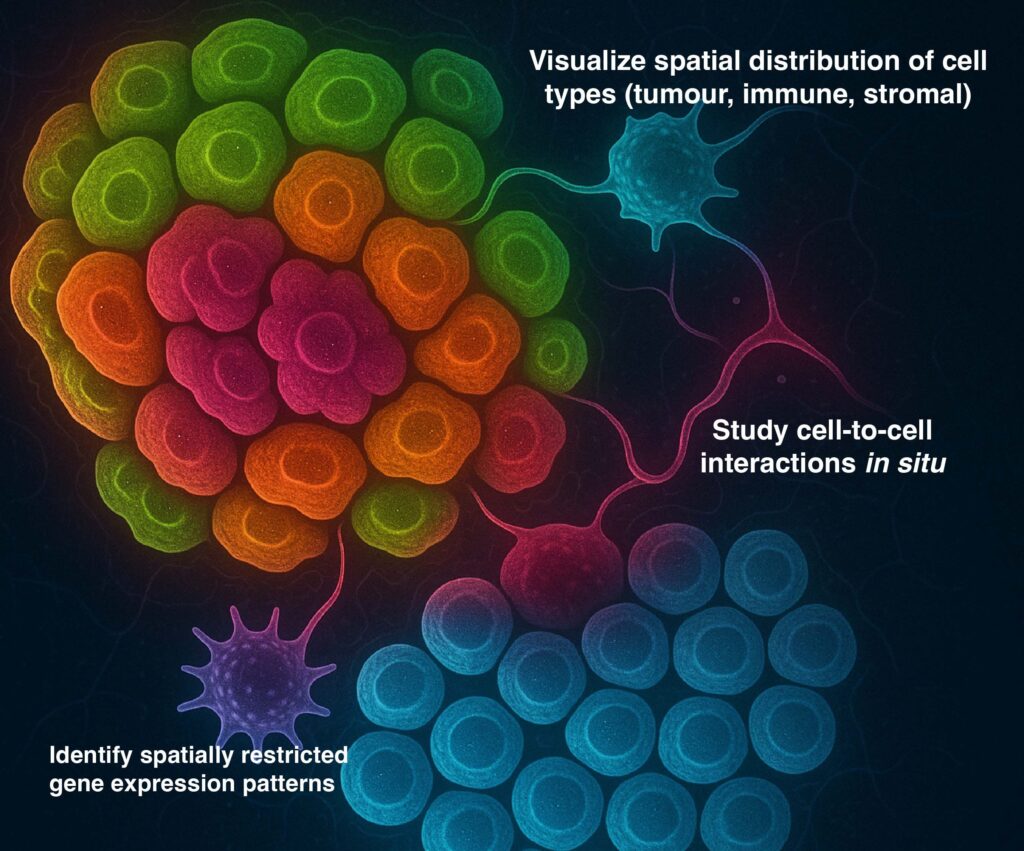

2. Lack of Spatial Molecular Context

Another major challenge is that even when you have single-cell level data, you often lose spatial context — i.e., which cells neighbour each other within a tumour, where immune cells are located relative to tumour nests, which regions are hypoxic, how stroma and tumour interface, etc. Spatial context matters hugely in cancer: cell–cell interactions, microenvironment niches, gradients of oxygen/metabolites, immune infiltration patterns all influence tumour biology and response to therapy.

The gap: Single-cell + loss of location

When tissues are dissociated for scRNA-seq, spatial information is lost. You know what cell types are present and their gene signatures, but you don’t know where those cells were within the tumour architecture. That missing spatial map can lead to incomplete interpretation of how tumour-stromal, tumour-immune, or vascular niche interactions drive progression or therapy resistance.

How spatial transcriptomics (ST) addresses this

Spatial transcriptomics technologies map gene expression back onto tissue sections, preserving the architectural context. This means you can:

-

Visualise spatial distribution of cell types (tumour, immune, stromal) within a tissue section;

-

Study cell–cell interactions in situ (e.g., immune-tumour contacts, fibroblast–tumour interactions, vascular interfaces);

-

Identify spatially restricted gene expression patterns (for example at tumour margins vs core, or immune-cold vs immune-hot zones) which may have prognostic or therapeutic relevance.

For instance, a 2023 review discusses technical advances in spatial transcriptomics in cancer and neuroscience. Wiley Online Library

Also, a 2024 review emphasises the application of ST in cancer research: unraveling intra-tumoral heterogeneity and tumour–stroma crosstalk. BioMed Central+1

Key takeaway

If your cancer research involves tumour architecture, immune infiltration, microenvironment niches or therapy response in spatial context, spatial transcriptomics is a powerful complement (or sometimes alternative) to purely dissociative single-cell methods.

3. Missing Complex Variants, Phasing and Structural Regions with Short-Read Sequencing

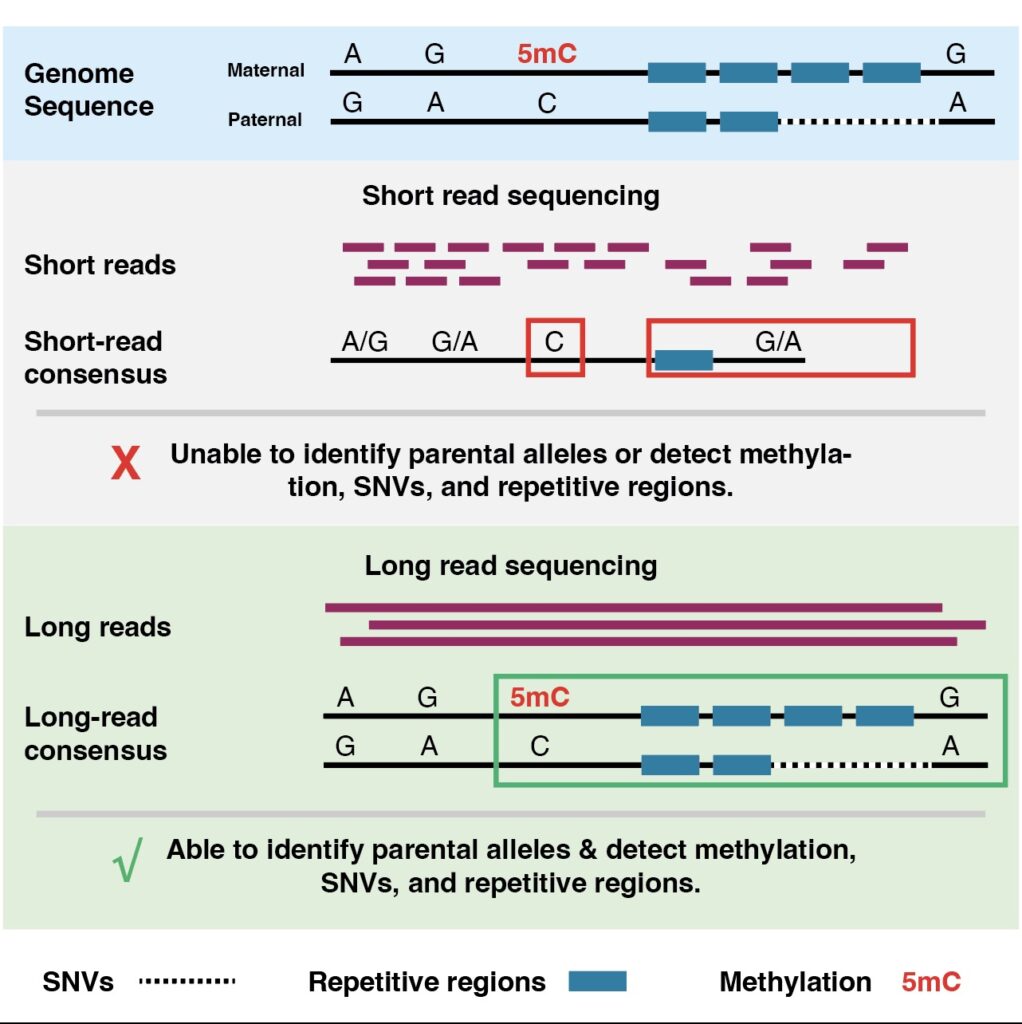

While RNA-based approaches (single-cell and spatial) cover transcriptomic and some cellular behaviour information, cancer genomes feature complex structural variants (SVs), large insertions/deletions, gene fusions, repetitive region expansions, extrachromosomal DNA, and haplotype phasing issues — many of which are poorly resolved by standard short-read next-generation sequencing (NGS).

The limitation of short reads

Short-read sequencing (e.g., 150-250 bp reads) is incredibly powerful and cost-effective, but has difficulties in certain contexts:

-

resolving large structural rearrangements (e.g., >10 kb inversions, large duplications, extrachromosomal circular DNA) because reads are too small to span the variant;

-

phasing haplotypes across long distances (maternal vs paternal allele) which matters for cancer in terms of LOH or allele-specific expression;

-

resolving highly repetitive or GC-rich/AT-rich regions, which may harbour oncogenic events;

-

accurately detecting some insertion/deletion (indel) classes or fusion gene architectures.

How long-read sequencing solves this

Emerging long-read sequencing technologies (for example from Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) produce reads tens to hundreds of kilobases long, enabling:

-

detection of large structural variants and complex genomic architectures;

-

phasing of haplotypes and improved allele-specific insight;

-

detection of fusion genes, circular DNA elements, viral integrations;

-

better resolution of repetitive regions or segmental duplications relevant to oncogenesis.

A 2023 study in colorectal cancer using nanopore long-read sequencing found on average ~494 somatic structural variants per sample, significantly more than what short-read studies detect. PLOS

Another review in 2023 focuses on resolving complex SVs via nanopore sequencing. Frontiers

Key takeaway

For cancer genomics research, especially when structural variation, gene fusions, extrachromosomal DNA or haplotype phasing matter (which is often the case), long-read sequencing is increasingly essential — or at least should be considered for key samples.

Conclusion

In summary, the three major technological pillars — single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and long-read sequencing — address three core challenges in cancer research:

| Challenge | Traditional limitation | Technological advance |

|---|---|---|

| Tumour heterogeneity | Bulk RNA-seq masks sub-clones | Single-cell sequencing resolves cell-level diversity |

| Loss of spatial context | Dissociated cells lose architecture | Spatial transcriptomics retains tissue context and cell neighbourhoods |

| Complex genomics (SV, phasing, repeat regions) | Short-read sequencing misses large/complex variants | Long-read sequencing detects structural variants, haplotypes and repeats |

By integrating these technologies, cancer researchers gain a more multi-dimensional view of tumour biology: cellular, spatial and structural. This enables deeper insights into the mechanisms of cancer initiation, progression, therapy resistance and metastasis — ultimately supporting precision oncology, biomarker discovery and targeted therapeutic strategies.

If you’re planning your next research campaign or content piece (for email marketing, social media or workshop materials) around cancer research, single-cell, spatial and long-read sequencing, this layered narrative will resonate with both technical and strategic audiences — especially when supported by recent peer-reviewed evidence (as cited above).